From Pistons to Growlers

On Jan. 17, 1941, almost 11 months before the United States entered World War II, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) asked the commandant of the 13th Naval District to find a location for the re-arming and refueling of Navy patrol planes operating in defense of Puget Sound, should such defense be necessary.

Lake Ozette, Indian Island, Keystone Harbor, Penn Cove and Oak Harbor were considered and later rejected because of mountainous terrain, bluff shorefront, inaccessibility, absence of sufficient beaches and lee shores.

But within 10 days, the commanding officer of Naval Air Station Seattle recommended the site of Saratoga Passage on the shores of Crescent Harbor and Forbes Point as a base suitable for seaplane takeoffs and landings under instrument conditions.

A narrow strip of land tied Oak Harbor to what is now Maylor’s Capehart Housing. Dredging, filling and running water and power lines to the city were underway when at the end of November word came to find a land plane site.

Clover Valley

On December 8, three workers started a topographic survey of what would become Ault Field, about four miles to the north. The crew would soon grow to 17. None of them were engineers, but with the attack at Pearl Harbor, the prior day, everyone went to work. Regardless of the weather, there were 175 men on the job at the peak of survey work.

Bewildered citizens, caught up in the war effort, signed up for jobs to build the station. There were approximately 20 farms on 4,325 acres. Farmers turned over the titles to their family lands, known for growing some of the finest wheat in the country, to the government for runways and hangars.

Clover Valley — level, well drained and accessible from any approach — seemed tailor-made for a landing field. The strategic location, commanding the eastern end of the Straits of Juan de Fuca, guarded the entrance to Puget Sound. It was far enough from populated areas to carry on operational training flights with live loads. The area experienced visual flying conditions about 89 percent of the time, and there was plenty of room to grow.

Actual construction of Ault Field started March 1, 1942. The first plane landed there August 5, when Lt. Newton Wakefield, a former civil engineer and airline pilot who would later become operations officer, brought his SNJ single-engine trainer in with little fanfare. Everyone was busy working on the still-incomplete runway.

Commissioning Day

On Sept. 21, 1942, from the steps of Building 12, Commanding Officer Capt. Cyril Thomas Simard read the orders and the watch was set. U.S. Naval Air Station Whidbey Island was duly commissioned. There were 212 present for the ceremony.

To honor Simard’s legacy, the CNO approved NAS Whidbey Island’s request to rename Building 12 as “Simard Hall.” Two of Simard’s granddaughters attended the official dedication on June 12, 2010.

On Sept. 25, 1943, following the recommendation of the Interdepartmental Air Traffic Control Board, an area 2½ miles southeast of Coupeville was approved as an auxiliary field to serve Naval Station Seattle. Survey work began in February 1944, and work started in March. Outlying Field Coupeville was in use by September.

Crews surveyed the Rocky Point area in the summer of 1944. It became the transmitter and machine gun range. Air gunners going to the fleet were trained there.

Patriotic fervor ran high in the early 1940s. The need to train America’s fighting force in a hurry was evident here on Whidbey Island.

PBY Catalina

Squadrons of PBY Catalinas began operation from the Seaplane Base in December 1942 when Lt. J.A. Morrison brought in the first PBY. These squadrons flew to Dutch Harbor, Cold Bay, Umnak, Nazan Bay, Adak, Amchitka, Shemya and Attu.

Like big flying boats, PBYs took off with a churning of water and a roar of engines for their practice runs in Saratoga Passage, then returned, skimming the hill above the hangar and settling into the bay to repeat the maneuver.

Residents of Oak Harbor soon became accustomed to the circling bombers training for the real thing in the Aleutian Islands. And with the attack by the Japanese there, a real concern gripped Alaska and the Pacific Northwest.

Bob Walker first set foot on Whidbey Island in 1944 to attend aerial gunnery school, followed by a tour with training squadron VPB-61 at the Seaplane Base. He described his job as sitting in the PBY-5A aircraft’s “tower,” which was the heart of the plane. “That’s where the engines were started and things like the fuel system, wingtip floats and slats were monitored. The PBY took off at 75, climbed at 75 and flew at 75. It was low and slow.”

Walker, an aviation machinist’s mate second class, later worked with HL-10, performing hydraulic and structural maintenance on the PB4Y-2 aircraft in 1945. “We’d spend six months here and then three months in Kodiak, Alaska, on patrol.”

Members of Patrol Wing 4 still tell stories of their Catalinas and Venturas being shot down and their crews killed, wounded or captured on their hunt for the Japanese during World War II.

Retired Cmdr. Ellis Skidmore of VPB-61 recalled, “Our PBY Catalinas carried a lot of cold-weather gear, plus four square-nosed depth charges, which made us 2,000 pounds over maximum gross when we took off. As dawn came up, our planes would be lined up, ready to take off. We could tell when the plane ahead of us left the runway because the plane would settle down over the water to where only the exhausts on top of the engines were visible to us. I can still remember that sinking feeling as our plane settled below the runway. We would stay on full power as the wheels came up and we kept the yoke pulled back to start our rate of climb at 75 feet per minute until we got up to our cruising altitude of 200 feet. Sometimes we’d fly like that for 10 hours, almost eyeball-to-eyeball, looking for submarine periscopes and shipping.”

Patrol planes flew long-range navigation training missions over the North Pacific. Fighters and bombers made bombing, rocket and machine gun attacks on targets in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Torpedo overhaul equipment was transferred to NAS Whidbey Island unexpectedly in 1942 from Indian Island, Washington. At the start, the torpedo shop refurbished six torpedoes per day. By January 1945, production had increased to 25 per day.

At the Seaplane Base, several PBM seaplanes were aboard in the summer of 1944 a few B-26s arrived earlier that year to tow targets for gunnery practice.

Wildcats and Hellcats

Over at Ault Field, the earliest squadrons of aircraft were F4F Wildcats, which came aboard in 1942, followed by F6F Hellcats. Later that year, PV-1 Venturas arrived for training. By the end of 1943, the F4Fs were gone, replaced by the F6F Hellcats. In 1944, SBD Dauntless dive-bombers became the predominant aircraft at Ault Field.

World War II Ends

From 1945 to 1950, three patrol bomber squadrons (VPHL-7, VPHL-10 and VPHL-12) were based here along with Fleet Aircraft Service Squadron (FASRON) 12. Squadrons deployed on a three-up and six-month-back rotation from Kodiak, Alaska. Regular patrols were flown in support of the Arctic supply operation and electronic reconnaissance from Nome down the dateline to Adak.

Squadrons were supplemented by the phase-in of P-2V squadrons in 1949. Squadrons were renumbered from HL-7 to VP-20, HL-10 to VP-27 and HL-12 to VP-29. They were decommissioned in early 1950 and replaced by P-2V squadrons. When the Korean conflict broke out, PB4Y-2s were again stationed at Whidbey as a replacement training group for patrol bombers.

Originally commissioned as a temporary station, NAS Whidbey Island’s operations slowed at war’s end. It was almost certain the base would be earmarked for decommissioning. Many bases were closing because they couldn’t meet the requirements of the new Air Navy: 6,000-foot runways were now the minimum standard, and approach paths had to be suitable for radar-controlled approaches in any weather. In December 1949, the Navy decided that while Naval Station Seattle, the major pre-war naval installation in the Northwest, was suitable to train Reserve forces and support a moderate number of aircraft, it could not be expanded as a major fleet support station.

Thus NAS Whidbey Island was chosen as the only station north of San Francisco and west of Chicago for this all-type, all-weather Navy field to support fleet and Alaska activities.

Neptunes & Marlins

Taken out of reduced operating status, Whidbey had a new lease on life. Expansion and construction accelerated with the Korean conflict.

P-2V Neptune patrol bombers, which arrived in the late 1940s, would eventually make up six patrol squadrons here. VP-50 moved up from Alameda in June 1956, returning seaplanes to NAS Whidbey. Flying the P5M-2 Marlin, patrol squadrons dominated the base until the 1960s.

Heavy Attack-Tankers

During the Korean War, patrol activity was stepped up again with several Reserve units being called up and then redesignated active squadrons. By the end of the war, there were six VP (Patrol) squadrons and two Fleet Air Support squadrons here.

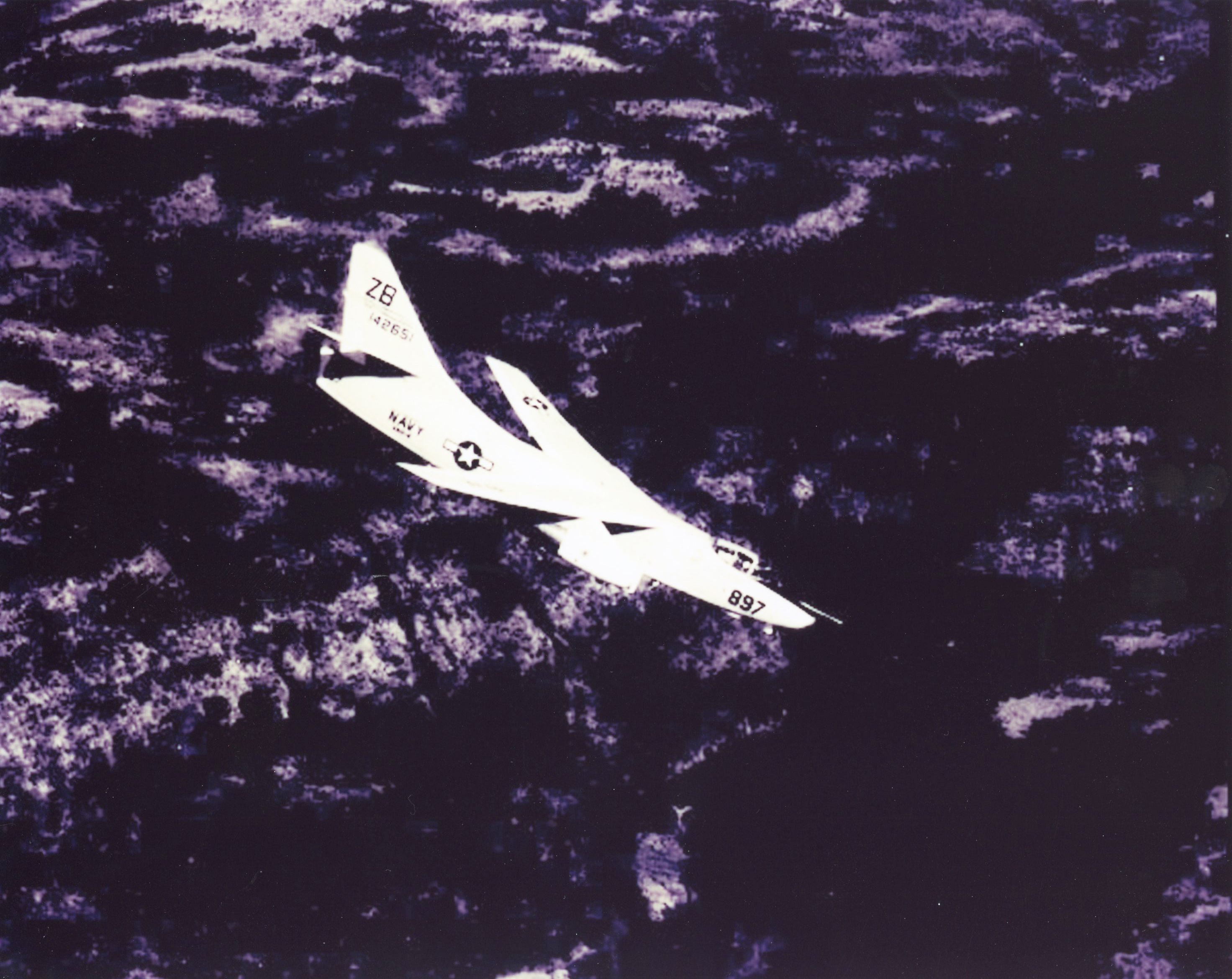

In 1955, VP-29 returned from deployment to the Pacific and was redesignated Heavy Attack 2, or VAH-2, the first heavy attack squadron on the West Coast. Later that year, it moved to San Diego to transition to the A-3D Skywarrior. In December 1956, the first A-3D Skywarrior was delivered to Whidbey to be flown by VAH-4. VAH-8 was commissioned here on May 1, 1957. In July 1957, Heavy Attack Wing 2, VAH-2 and Heavy Attack Training Unit, Pacific, were transferred from NAS North Island, California, to NAS Whidbey Island to form the nucleus of the Navy’s Pacific Fleet heavy attack program.

VAH-6 came up from North Island on Jan. 15, 1958, and became the first heavy attack unit to deploy to the Far East with the A-3D. By the end of 1958, heavy attack squadrons outnumbered patrol by 5 to 4. That number continued to grow with the commissioning of VAH-10 on May 1, 1961, and the transfer of VAH-13 here from Sanford, Florida. All flew the Skywarrior.

The “Whales” were the backbone of attack aviation until the arrival of the A-6A Intruder in August 1966. VAH-8 was decommissioned on Jan. 17, 1968; VAH-2 and 4 changed homeport to NAS Alameda on Sept. 13, 1968, and on Nov. 1, 1968, they became Tactical Electronic (VAQ) squadrons 132 and 131, respectively.

Patrol squadrons began to leave in early 1965; VP-47 went to Moffett Field and VP-17 to Barbers Point. In July 1969, the patrol community appeared to be reviving with the delivery of the P-3 Orion as a replacement for the P-2. That September, VP-2 and VP-42 were deactivated. On March 1, 1970, VP-1 moved to NAS Barbers Point, ending patrol operations by active forces at NAS Whidbey Island. This also brought Fleet Air Wing 4 to an end on April 1, 1970.

Flying Workhorse

The Grumman A-6 Intruder served the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps as their primary all-weather attack aircraft for more than 30 years. Brought into service during the Vietnam War, the Intruder saw action in every major crisis since, most recently the Gulf War. The aircraft immediately developed a reputation for reliability, durability and accuracy that persisted throughout its long years of service. The Marine Corps phased the Intruder out of its inventory shortly after Operation Desert Storm. In all, 16 Navy squadrons maintained and operated this flying workhorse. Whidbey was the West Coast training and operations center for these all-weather, medium-attack bomber squadrons.

Attack Squadron 196 became Whidbey’s first squadron slated to receive the A-6A on Nov. 15, 1966. VA-165 and VA-145 reported aboard on Jan. 1, 1967, to transition from the A-1 to the A-6. VA-52 reported aboard on July 1, 1967, and VA-128, the A-6A fleet replacement squadron for Commander, Naval Air Force, Pacific Fleet, was commissioned after splitting from VAH-123 on Sept. 1, 1967. On Jan. 1, 1970, VA-115 came to Whidbey and VA-95 came on April 1, 1972, bringing the total number of A-6 squadrons here to seven.

VA-196 became the last A-6 squadron to retire on Feb. 28, 1997. The Intruder saw service in Vietnam, Libya and Desert Storm. At one time, NAS Whidbey Island had as many as 125 A-6 aircraft.

Electronic Attack

With the departure of Whidbey-based A-3D Skywarriors, the EA-6B Prowler came into prominence at the air station. In October 1970, VAH-10 was redesignated Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 129, the Navy’s first EA-6B squadron and the training squadron for Prowler crews.

Since its initial deployment to Southeast Asia in 1972, the Northrop-Grumman EA-6B Prowler assumed the primary mission of strike aircraft and ground troop support. Through employment of the Prowler’s highly specialized electronic intelligence receivers and jamming equipment, the EA-6B degraded or destroyed enemy radar and command and control capability, enabling safe passage of friendly strike aircraft. Capable of carrying the AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM), the Prowler brought a formidable depth to its Electronic Attack (EA) arsenal. In addition to jamming pods and HARM, the Prowler carried externally mounted chaff pods and fuel tanks. In the EA role, the Prowler usually carried a mix of five of the previously listed stores, tailored to specific mission requirements.

NAS Whidbey Island was home to the Navy’s Prowler community, and now the only base for all the new EA-18G Growler fleet. Currently, there are 14 Growler squadrons, eight of which deploy to aircraft carriers, four expeditionary squadrons not assigned to carrier air wings, one Whidbey-based training squadron, and one reserve squadron.

Expeditionary squadrons deploy in support of joint forces from land bases in the Mediterranean area and Middle East. As the U.S. Air Force EF-111A Raven fleet was phased out of service in 1995, Air Force personnel from that program have integrated into these expeditionary squadrons and VAQ-129.

Growler Arrives

The replacement aircraft for the EA-6B made its first appearance April 9, 2007. The rollout began June 3, 2008, as the first Boeing Growler arrived on station. The airborne electronic attack aircraft combines the state-of-the-art two-seat, twin-engine F/A-18F Block 2 Super Hornet with the Improved Capability III system to provide next-generation electronic attack capability.

The transition of the Prowler to the Growler aircraft was completed in 2015, with VAQ-132 being the first to complete the transition and VAQ-134 being the last. A $49.2 million renovation project of Hangar 5 to modernize the 1953-1954-era structure for the Growler squadrons was completed in May 2010. Following a DOD assessment and subsequent Congressional action, the Navy's Growler fleet grew from an initial allotment of 72 aircraft to a total of 118.

Support Aircraft

The air station maintains a Search and Rescue Unit, flying three MH-60S Knighthawk helicopters that arrived in the summer of 2005. Previously, the unit flew SH-3H Sea Kings and H-46 Sea Knights.

In May 1970, the first Naval Reservists from NAS Sand Point arrived as air activities ended there. Naval Air Reserve Training Unit and Marine Air Reserve Detachment were officially welcomed aboard on May 14, 1970, signaling the station’s role as a Reserve training center in the Northwest. In addition to the Growler reserve squadron, other reserve units operating from NAS Whidbey Island include; one reserve patrol squadron that flies the P-3C, and a Fleet Logistic Support squadron that transitioned from the C-9 Skytrain to the C-40 Clipper.

Thirty six tenant commands are located at NAS Whidbey, providing training, medical and dental, and other support services.

Maritime Patrol

Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing 10 relocated to NAS Whidbey Island in December 1993 when NAS Moffett Field closed, and was reduced to two patrol squadrons, VP-40 and VP-46. NAS Agana, Guam, closed in 1994, which brought Fleet Reconnaissance Squadron VQ-1 and their EP-3E Aries II aircraft to the Wing 10 family, at which point Patrol Wing 10 became Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing 10.

In 1995, VP-1 joined the wing out of NAS Barbers Point when that base closed.

After 45 years at Naval Station Rota, Spain, VQ-2 relocated to Whidbey on Oct. 1, 2005. They came with six aircraft and 450 Sailors. The move was part of a Navy-wide plan to streamline itself, and improve efficiency and operational capabilities of both VQ-1 and VQ-2. VQ-1 and VQ-2 were consolidated into one (VQ-1) in May 2012.

Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing 10 squadrons deploy to the 5th and 7th Fleet areas of responsibility, providing anti-submarine warfare, maritime patrol and reconnaissance support throughout the Pacific and Indian oceans, and extending into the Persian Gulf.

The Navy began the seven year transition from the P-3 Orion to the P-8 Poseidon in 2012. Part of the transition includes a consolidation of patrol squadrons from Hawaii that began with VP-4's arrival at NAS Whidbey Island in September 2016. VP-47 arrived in February 2017, and VP-9 completed the transition to NAS Whidbey Island later that year. All of the active duty P-3 squadrons successfully transitioned to the P-8 Poseidon by March 2020.